First the scientists dress dead swine in clothes, then they dispose of the carcasses. Some they wrap in packing tape, others they chop up. They stuff the animals into plastic bags or wrap them in blankets. They cover them in lime or burn them. Some are buried alone, others in groups.

Then they watch.

The pigs play an unlikely role in research to help find the staggering number of people who went missing in Mexico during decades of drug cartel violence.

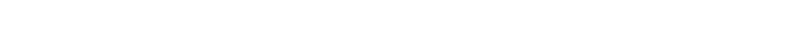

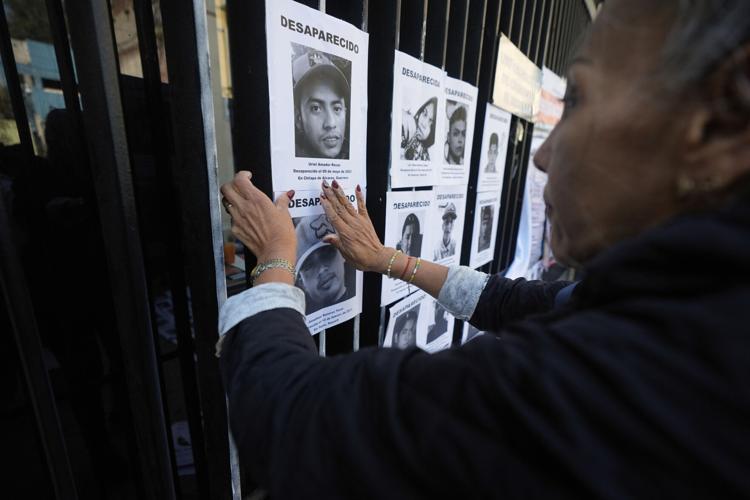

Demonstrators tape images of missing persons to a Senate building gate April 10 in Mexico City.

Families of the missing were often left to look for their loved ones with little support from authorities. Now, government scientists are testing the newest satellite, geophysical and biological mapping techniques — along with the pigs — to offer clues that they hope could lead to the discovery of at least some of the bodies.

130,000 missing

People are also reading…

The ranks of Mexico's missing exploded in the years following the launch of then-President Felipe Calderón's war against drug cartels in 2006. A strategy that targeted the leaders of a handful of powerful cartels led to a splintering of organized crime and the multiplication of violence to control territory.

With near complete impunity, owing to the complicity or inaction of authorities, cartels found that making anyone they think is in their way disappear was better than leaving bodies in the streets. Mexican administrations sometimes were unwilling to recognize the problem and at other times are staggered by the scale of violence their justice system is unprepared to address.

The relatives of missing people gather March 13 at Izaguirre Ranch to see if they can identify skeletal remains discovered in Teuchitlan, Jalisco state, Mexico.

Mexico's disappeared could populate a small city. Official data in 2013 tallied 26,000 missing, but the count now surpasses 130,000 — more than any other Latin American nation. The United Nations said there are indications the disappearances are "generalized or systematic."

If the missing people are found — dead or alive — it is usually by their loved ones. Guided by information from witnesses, parents and siblings search for graves by walking through cartel territory, plunging a metal rod into the earth and sniffing for the scent of death.

About 6,000 clandestine graves were found since 2007, with new discoveries all the time. Tens of thousands of remains have yet to be identified.

Testing solutions

Jalisco, home of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel, has the largest number of people reported missing in Mexico: 15,500.

In March, human bone fragments and hundreds of items of clothing were discovered at a cartel ranch in the state. Authorities denied it was a mass grave site.

Danger warning tape is seen July 11 near a ranch where prosecutors say bodies were discovered in a mass grave in the Zapopan municipality, Jalisco state, Mexico.

José Luis Silván, a coordinator of the mapping project and scientist at CentroGeo, a federal research institute focused on geospacial information, said Jalisco's disappeared are "why we're here."

The mapping project, launched in 2023, is a collaboration by Guadalajara University, Mexico's National Autonomous University and the University of Oxford in England, alongside the Jalisco Search Commission, a state agency that organizes local searches with relatives.

"No other country is pushing so strongly, so creatively" to test and combine new techniques, said Derek Congram, a Canadian forensic anthropologist whose expertise in geographic information systems inspired the Mexican project.

Still, Congram warns, technology "is not a panacea."

"Ninety percent of searches are resolved with a good witness and digging," he said.

A member of the State Commission for the Search for Missing Persons collects insects July 10 within the experimental grounds in Cajititlan, Mexico, to gather information about clandestine graves.

Looking for signs

Silván walks by a site where scientists buried 14 pigs about two years ago. He says they may not know how well the technology works, where and when it can be used, or under what conditions, for at least three years.

"Flowers came up because of the phosphorous at the surface, we didn't see that last year," he said as he took measurements at one of the gravesites. "The mothers who search say that that little yellow flower always blooms over the tombs and they use them as a guide."

Pigs and humans are closely related, sharing about 98% of DNA. For the mapping project, the physical similarities also matter. According to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, pigs resemble humans in size, fat distribution and the structure and thickness of skin.

A specialist on examines insects collected from clandestine graves in Jalisco on July 11 in Guadalajara, Mexico.

A big Colombian drone mounted with a hyperspectral camera flies over the pig burial site. Generally used by mining companies, the camera measures light reflected by substances in the soil — including nitrogen, potassium and phosphorus — and shows how they vary as the pigs decompose. The colorful image it produces offers clues of what to look for in the hunt for graves.

Researchers also employ thermal drones, laser scanners and other gadgets to register anomalies, underground movements and electrical currents. One set of graves is encased behind transparent acrylic, so scientists can observe the pigs' decomposition in real time.

The Jalisco commission compares and analyzes flies, beetles, plants and soil recovered from the human and pig graves.

Each grave is a living "micro ecosystem," said Tunuari Chávez, the commission's director of context analysis.

A specialist examines crawling creatures collected from clandestine graves as part of a research project July 11 in Guadalajara, Mexico.

Solving problems

Triggered by the disappearance of 43 students in 2014, Silván and his colleagues started gathering information about ground-penetrating radar, electric resistivity and satellite imagery from around the world. They studied University of Tennessee research on human corpses buried at a "body farm." They looked at grave-mapping techniques used in the Balkans, Colombia and Ukraine.

"What good is science or technology if it doesn't solve problems?" he said.

A member of the State Commission for the Search for Missing Persons collects insects July 10 within the experimental grounds in Cajititlan, Mexico.

They learned new applications of satellite analysis, then began their first experiments burying pigs and studying the substances criminals use to dispose of bodies. They found lime is easily detected, but hydrocarbons, hydrochloric acid and burned flesh are not.

Chávez's team worked to combine the science with what they knew about how the cartels operate. For example, they determined that disappearances in Jalisco commonly happened along cartel routes between Pacific ports, drug manufacturing facilities and the U.S. border, and that most of the missing are found in the same municipality where they disappeared.

Mutual helpers

The experience of the families of the missing also informs the research.

Some observed that graves are often found under trees whose roots grow vertically, so those digging the graves can remain in the shade. Mothers of missing loved ones invited by researchers to visit one of the pig burial sites were able to identify most of the unmarked graves by sight alone, because of the plants and soil placement, Silván said.

“The knowledge flows in both directions,” he said.

The relative of a missing person waits March 13 to enter Izaguirre Ranch to see if any of the skeletal remains discovered here are identifiable in Teuchitlan, Jalisco state, Mexico.

Maribel Cedeño, who has been looking for her missing brother for four years, said she believes the drones and other technology will be helpful.

"I never imagined being in this situation," she said, "finding bodies, becoming such an expert."

The Jalisco Search Commission already uses a thermal drone, a laser scanner and a multispectral camera to help families look for missing relatives. Still, it is unclear whether authorities will be willing to use — or able to afford — the high-tech aides.