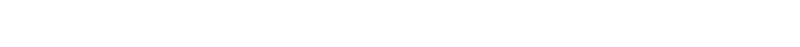

A University of Nebraska-Lincoln study found people living in mobile homes in Douglas, Sarpy and Dodge Counties are disproportionately more likely to experience flooding than residents in other housing structures.

The study, which was prompted by the devastating effects of the 2019 floods and authored by postdoctoral researcher Jesse Andrews, found thousands of mobile home residents remain in federally designated flood hazard areas. That includes 1,230 residents who mostly reside in mobile homes near the Platte and Elkhorn Rivers in Fremont and the Missouri River in northeast Omaha. Mobile home residents in Valley are also especially at risk.

Floodwaters from the Platte River are seen rising into North Bend, Nebraska, on March 15, 2019.

According to the study, which looked at buildings from 23 mobile home parks, nearly 20% of mobile homes in Douglas County and 50% in Dodge County are in high-risk flood zones. A lack of flood prevention infrastructure also puts many mobile home parks at risk.

People are also reading…

For example, according to the study, Dodge County has no levees protecting its mobile home parks. Mobile home residents in Douglas County are somewhat protected by a levee system in place.

The study did not look into why some areas have infrastructure to protect their residents from floods while others don’t, said Zhenghong Tang, a UNL community and regional planning professor who led the study’s research team.

There could be many reasons, he said, including a lack of public awareness about how vulnerable their communities are to flooding even after the region suffered more than $1 billion in damage from the 2019 floods, which lasted from March to July. At one point, a UNL press release noted, floodwaters cut off access to Fremont. One mobile home park in Sarpy County shut down permanently after a levee failed.

The demographics of mobile home residents may also play a role, as many are lower income and often renters.

Even though the 2019 floods are still in recent memory, researchers found continued development of mobile home parks in high-risk flood areas. The study found that, from 2018 to 2024, the number of mobile homes grew by nearly 18% in Dodge County, nearly 8% in Douglas County and 6% in Sarpy County.

This map from a University of Nebraska-Lincoln study shows flood prone mobile home parks in Douglas, Sarpy and Dodge Counties.

The UNL press release announcing the study’s findings noted a variety of factors for continued development in risky areas, including a chronic shortage of affordable housing pushing low-income families into flood-prone parks. Local governments have also allowed new parks to be built and existing ones to remain in known flood zones.

Tang said Nebraska needs to offer more affordable housing resources, including more housing not located in flood-prone areas and offering buyout programs and relocation assistance to those who currently live in flood-prone areas.

“Affordable housing is a critical need for the state, economy and the people. We are still short of housing supplies,” Tang said.

The study also called on communities and counties to invest in levees and drainage systems.

Unfortunately, Tang acknowledged, reality often comes back to bite. He noted insurance companies require homeowners build their structures back to the previous level on the same properties destroyed by flooding. Many affordable housing developments are built in flood-prone locations due to the land being cheaper.

As long as residents are living in flood-prone areas, Tang said, the region is taking greater risks.

“If any disaster will happen someday, taxpayers will pay more money for the rescue, response and recovery,” he said.

Flood of 2019: The aftermath and the recovery

Nebraska’s disastrous weather in 2019 caused more than $3.4 billion in losses, according to a recently released federal report. Read more

A 92-year-old dam that collapsed March 14, 2019 amid had been classified by state inspectors last year as having a “significant” risk of causing damage.

A man who lived in a home below the dam, Kenny Angel, was swept away in the collapse and is presumed dead, and a quarter mile section of U.S. Highway 281 was washed out. Read more

A four-member team from the Association of State Dam Safety Officials, a national nonprofit organization, will conduct an independent review of the Spencer dam.

The review will focus on what can be learned about the dam collapse to guide future dam construction, according to Lori Arthur, a spokeswoman for the Natural Resources Department. Read more

Even the U.S. Air Force couldn’t stop the Mighty Missouri River from flooding Offutt Air Force Base. Between March 16 and 17 sandbagging efforts were called off as flood waters began to rise. Read more

Six months after what 55th Wing officials describe as “historic and disastrous” flooding swamped one-third of Offutt Air Force Base and destroyed 137 structures, the expected costs of rebuilding continued to mount.

Lt. Col. Chris Conover, who spearheaded the recovery and reconstruction project, said in September that the figure stood at $790 million in September. He warned the cost most likely would rise further — perhaps even hitting $1 billion. Read more

The Platte River swelled into Fremont, turning the city into an island.

Shelters in Fremont alone counted up to 1,100 people, with more evacuees expected from Snyder, Nebraska. And those numbers don’t capture the swaths of people riding out the flood in hotel rooms or crashing on the couches of family and friends.

Those who decided to evacuate left by plane, train line and automobile. There were departures by boat, by airboat and by massive military vehicles with jacked-up frames capable of cruising through waterlogged roads. Read more

Hundreds of people filled Christensen Field Arena in Fremont to hear a National Weather Service update on this year’s flood risk Feb. 4.

The crowd received a nuanced, but somewhat reassuring, explanation from National Weather Service hydrologist Dave Pearson. Read more

Before the water even reached the community, Paradise Lake residents were sent mixed messages.

Law enforcement officials went door to door encouraging residents to evacuate, Paradise Lakes residents received a different message from their landlord: Your homes are safe. Read more

The Bellevue City Council voted to condemn the community and told residents that they had until the end of July to take action on removing their homes. The remaining structures were expected to be razed by a city-hired company in early August.

Jim Ristow, Bellevue’s city administrator, said in August that officials are now taking a cautious approach moving forward because they don’t want taxpayers to be on the hook for the estimated $1.2 million needed for demolition.

Paradise Lakes’ owner, Howard “Howdy” Helm, has told the city that he can’t afford the cost of demolition. Read more

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers sought bids to close the breach in the south bank of the Platte River that had stranded the city’s water treatment plant during the March flooding.

For months, the plant was accessible only by boat. Now, the water is gone, but Plattsmouth officials have wondered for how long. Read more

Plattsmouth notched a major victory in September when its flood-battered water treatment plant got back up and running, ending months of water rationing.

But the city’s ongoing battle with the waters of the Platte River isn’t over. Read more

Winslow floods.

One in 1996 brought water inside town and into basements, but it was nothing like the surge of water that clobbered Winslow in mid-March, when historic flooding struck parts of central and eastern Nebraska.

So the residents of this little village — where the population that hovered around 100 before disaster struck — are pondering a pivotal question about its future. Go should they stay or should they go? Read more

A group of state and federal officials who met in Winslow in January said plenty of hurdles stand in the village's way.

Those obstacles include state law, the likely millions of dollars needed to put in new streets and utilities in Winslow 2.0 and its dwindling population.

"We all want what's best for Winslow, I want to make that abundantly clear," said Molly Bargmann, a recovery supervisor for the Nebraska Emergency Management Agency. "We want to get to yes, but there's a lot of no's right now." Read more

On St. Patrick’s Day weekend 2019, a violent chute of water raged through a gash in the levee that for decades protected the Nebraska National Guard’s main training site from the Platte River. Floodwaters surged into classrooms, barracks and offices, wrecking furniture and tools and leaving a muddy watermark 5 feet high on inside walls.

The Nebraska National Guard learned in January that it will receive full funding, totaling $62.3 million, to fully rebuild the Camp Ashland training site, according to a statement released Wednesday by the state’s adjutant general, Maj. Gen. Daryl Bohac. Read more

Tons of sand, sediment and silt — some in dunes as high as 10 feet — were scattered across the eastern half to two-thirds of the state by the March flooding. In some areas, washed-out cornstalks are 3 to 4 feet deep. Tree limbs are in piles and topsoil was washed away. Read more

Trish and Salvador Duran hosted Christmas this year for their extended family, an act of hospitality that once seemed impossible after almost 4 feet of floodwater swept into their house in King Lake in March.

King Lake is an unincorporated area, a secluded neighborhood of 1 square mile that sits next to the Elkhorn River and not far from the Platte River, east of Valley and north of Waterloo. During historic flooding in March, the Elkhorn spilled out of its banks, sending water into almost all of the 111 homes in King Lake. Read more

Pacific Junction, with a population of less than 500, was hit hard by levee failures in March that sent floodwaters streaming into town, filling every structure with feet of water. It wasn't until mid-April that the last batch of residents could return to their homes and businesses and start clearing out flood-soaked possessions. Read more

Mills County Democrats worried all month whether many of the 470 former residents of this flooded town would attend a caucus Monday.

Last March, the Missouri River inundated all 210 homes and businesses here, and a caucus day drive through town showed the extent of damage 10 months later. Most local homes, storefronts and gathering spaces remain boarded up. Only about 20 households have moved back so far, officials say, and the only evidence of the presidential race was a single campaign sign in front of the rebuilt home of Rick and Cherry Parham. Read more